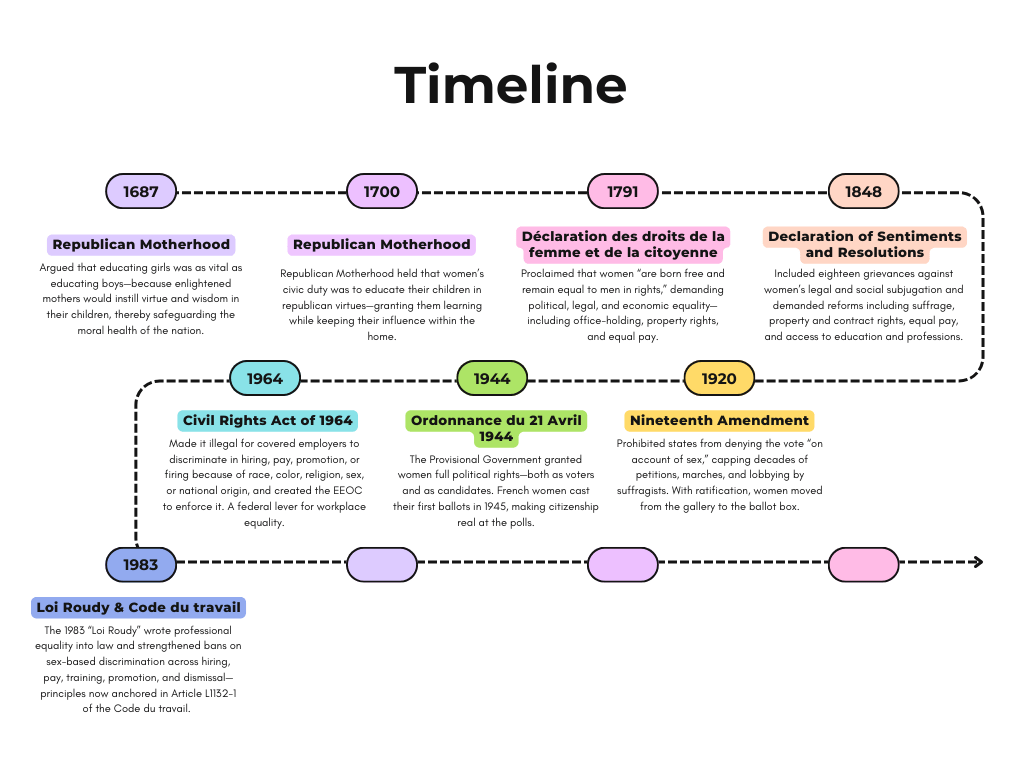

We still live in a male-dominated world, but the ground has shifted. What began as scattered acts of endurance has become coordinated campaigns—petitions, picket lines, court cases, and ballots—that press these two nations to honor their own ideals.

Nineteenth Amendment

Women have helped build the republic from the very start, yet it wasn’t util 1920 when they were finally recognized through the Consituiton. The 19th Amendment, passed by Woodrow Wilson after much pressure from the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association, decalred that states were prohibited from denying the right to vote “on account of sex”. This ment that the decades of petions, marches, and civil disobidence finally were acknoledged by the government. With ratification, women moved from lobbying in the gallery to shaping laws at the ballot box.

Ordonnance du 21 Avril 1944 – Droit de vote des femmes

Under the pressure of the second world war and complete French liberation, France ultimately recognized women as full political actors. After nearly a century of women’s suffragist protesting and yearning for the right to vote – like Hubertine Auclert, called “the first French Suffragist” – the Provisional Government’s 1944 ordinance granted women both the right to vote and to stand for office. The following spring, French women were able to cast ballots for the first time in municipal elections.

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII

Equality had to reach the workplace, too. In 1964, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, and Title VII made it illegal for employers to discriminate in hiring, pay, promotion, or firing because of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. The law also created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to investigate complaints and enforce these rules, generally covering employers with fifteen or more employees. With Title VII, women finally had a federal tool to pry open closed doors on the job.

Loi Roudy & Code du travail – égalité professionelle

France answered by writing equality straight into labor law. The 1983 “Loi Roudy” set professional equality between women and men as a rule and tightened bans on discrimination across hiring, pay, training, promotion, and dismissal. Today, Article L1132-1 of the “Code du travail” spells that out clearly and applies it across the whole employment relationship. In short, if you do the work, you deserve equal treatment at work.

Conclusion

Stepping back, the pattern is clear: both sides of the Atlantic moved from arguments about educating future citizens to demands for full political voice and equal standing at work. in the U.S., that arc runs from early agitation to the 19th Amendment in 1920, which finally put women’s suffrage in the Constitution. In France, the wartime ordonnance of April 21, 1944 recognized women as voters and candidates, with ballots cast the following year—same fight, different clock. Later, laws pushed equality into the workplace: Title VII of the Civil Rights Act (1964) barred employment discrimination “because of sex,” and France’s Loi Roudy and the modern “Code du travail” made professional equality an enforceable rule. The stories aren’t identical today either—France has now embedded abortion protection in its Constitution, while in the U.S. Dobbs ended federal constitutional protection and handed the issue to the states. but the through-line is persistence: women organizing, educating, litigating, and voting until ideals become rights—and then defending those rights when they’re tested.

Leave a comment